DRAFT White Paper

Privacy-Preserving

Travel Rule Compliance

Draft: July 6, 2021

Authors: John Jefferies, Harjasleen Malvai, Deepak Maram, Ben Whitby, The Tallest Man

Abstract

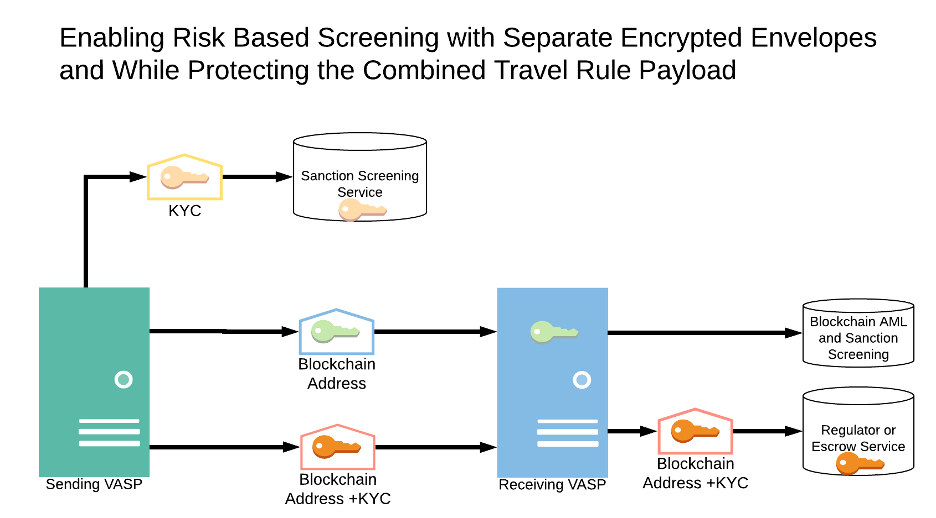

This whitepaper asserts that Travel Rule goals can be achieved without exposing Virtual Asset Service Provider (VASP) users to unnecessary privacy risks. Personally Identifiable Information (PII) of cryptocurrency senders and the associated blockchain attribution data do not need to be exposed unencrypted simultaneously during transmission in order for VASPs to comply with the Travel Rule and Risk Based Approach (RBA). By separating the sanction screening of legal persons from blockchain Know Your Transaction (KYT) obligations, the receiving VASP can comply with the Travel Rule and AML obligations while segregating the data elements during screening. This paper shows how encrypted envelopes and Zero Knowledge Proof can work together to allow entities to comply with the relevant regulations while protecting user privacy.

Privacy-Preserving Travel Rule Compliance

The Travel Rule and regulation of VASPs as financial institutions are inevitable. However, enforcing this compelled information sharing globally may have unintended negative consequences for the privacy of virtual asset users when implemented without adequate security controls and safeguards in place. Below we explore several such issues and consequences, propose privacy-enhancing travel rule solutions, and demonstrate a proof of concept for zero knowledge sanction screening.

Travel Rule Objectives

The US Travel Rule first became effective May 28, 1996, alongside new BSA recordkeeping rules for covered institutions. In 2014, US FinCEN extended the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) from financial services to cryptocurrency, but it has been minimally deployed and is most often enforced in conjunction with other egregious offenses.

In February 2019, Financial Action Task Force (FATF) released a Risk Based Approach to Virtual Assets and VASPs (RBA) with the objective of “preventing terrorists and other criminals from having unfettered access to electronically-facilitated funds transfers for moving their funds and for detecting such misuse when it occurs.” Part of this release included a change to Recommendation 16 (R.16) of the FATF Recommendations—the international anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) standards nations use to guide their AML/CFT policies. Colloquially known as the FATF Travel Rule, R.16 prescribes the sharing of sender and receiver PII to “stop criminals and terrorists who wish to use the speed and anonymity of virtual assets to launder the proceeds of their crimes and finance their illicit activities.”

The Travel Rule is intended to share information to allow participants to:

- Block terrorist and proliferation financing

- Stop payments to sanctioned individuals, entities, and countries

- Enable law enforcement to subpoena transaction details

- Support reporting of suspicious activities

- Prevent money laundering of virtual assets

The goal is to stop proceeds of crime—including ransom payments, illegal dark market sales, proliferation finance and terrorist financing—from using virtual assets as an anonymizing payment rail. Additionally, the Travel Rule enables authorities to block the conversion of virtual assets or identify the individuals that converted the crypto to cash.

Travel Rule Unintended Consequences and Privacy Issues

Sharing sensitive financial transaction data and client PII with unknown or untrusted VASPs creates numerous privacy issues for virtual asset users. As evidenced by dozens of successful exchange hacks, few VASPs are well prepared to defend against a dedicated adversary, and have poor security around crypto assets, let alone stored PII. Many smaller VASPs lack adequate security expertise and previously had not considered themselves to be financial institutions.

Risks to individual privacy and to personal safety are real since the shared information includes physical location and possibly the value of a user’s crypto in the context of the Travel Rule. Risks include:

- Hacks and PII data leaks

- Transaction IDs can be used to determine how much crypto the holder controls

- Physical and cyber attacks against holders

- Fake VASPs masquerading as legitimate VASPs to collect PII

- Harvesting, data mining, and selling user PII data

- Monitoring by oppressive regimes, leaks, hacks, data mining, poor security, oppressive regimes, data brokering

- DDOS and market manipulation

- Abuse of collected PII for identity theft

Virtual asset users are continuously attacked by phishing attempts, SIM swaps and compromised counterfeit wallets.In 2020, crypto wallet provider Ledger’s data leak of more than 270,000 wallet owners PII resulted in numerous phishing campaigns and physical deliveries of compromised hardware wallets to unsuspecting Ledger owners.

Proposed Solutions

Thesis:

The Travel Rule requires that information needs to be retained by each VASP but it does not have to be viewed by the receiving party nor does it need to be stored in clear text.

PII and transaction IDs of the sender do not need to be exposed simultaneously to comply with the Travel Rule. By separating the sanction screening of the legal person from blockchain Know Your Transaction (KYT) obligations, the receiving VASP can comply with the Travel Rule guidelines and AML obligations while segregating the data elements during screening. Sender PII and cryptocurrency addresses do not need to be exposed simultaneously to perform risk-based processes.

Assumptions

- Sending VASP and Receiving VASP must perform sanction check on all persons

- Sending VASP and Receiving VASP must perform AML and sanction check on the blockchain addresses

- Sending VASP and Receiving VASP can store the PII and addresses in encrypted envelopes to protect the data at rest

- Encryption Key Management Systems (KMS) deployed to provide security controls, lawful access and audit trails

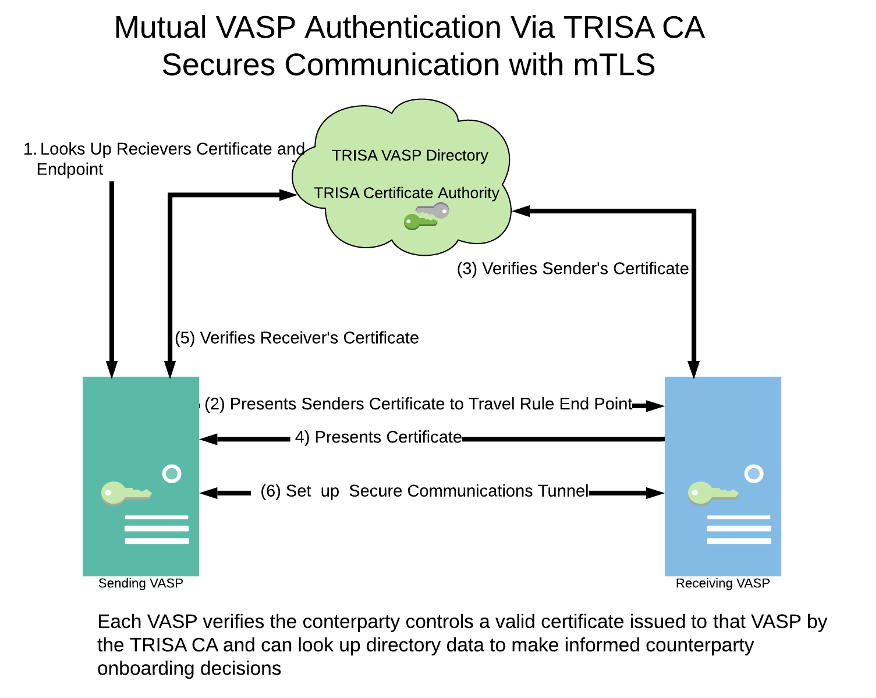

- Both VASPs possess valid TRISA KYV certificates, establish mutual authentication,and a secure mTLS communication channel

TRISA Encrypted Transaction Envelopes Protect User Information at Rest and In Motion

The peer-to-peer TRISA protocol defines a Transaction Data envelope that can be used to seal account holder data. This envelope applies additional encryption of the message and an HMAC digital signature. It can be used to send and encrypt data elements separately or combined in one envelope.

Although all messages are exchanged over a secure channel, by adding this additional layer VASPs can securely store the encrypted Transaction Envelope at rest in a backend of their choice while maintaining nonrepudiation of the exchange. Encrypted envelopes also enable the personally identifiable information and the blockchain attribution details to be transmitted separately for screening and together for archival and retrieval.

This approach would allow sanctions lookups on the users and AML check on the addresses without exposing the user details and address data at the same time during normal transaction processing.

Issue to be addressed:

- Requires key management to satisfy long term retention and recovery.

- Consider encrypting User details and Address data in one envelope but it will have to be opened for PEP and sanctions checks.

- Another option would be to encrypt User details and Address data with different keys. This approach exposes the recipient’s name and personal identifiers to the receiving VASPs

A possible solution to the secure storage of at rest Sender PII could be to transmit the encrypted envelope with two sets of encrypted data (or two envelopes). In this solution, one set of data contains basic info needed by the recipient VASP to match the envelope to a recent deposit, and the other set is more comprehensive. The recipient VASP would not have the keys to decrypt this second set of data. The government agencies that are requesters of the PII data would be in possession of keys at all times to decrypt this second set of PII data, but would only receive the encrypted PII data related to specific transfers when requested from the recipient VASP through the approved channels.

The unique issue is the secure storage of the Sender PII data which is in the possession of the Recipient (untrusted) VASP.

In this example, the Recipient untrusted VASP could not even open and view the secure portion of Transmittor’s PII because they don’t have the encryption key. The only parts of the incoming encrypted PII data envelope that the recipient VASP needs to see in order to match the data envelope to a recent deposit are the Recipient’s deposit address, amount, and a time stamp. These items could still be encrypted by the Sender, but be decryptable by the Recipient VASP, while the remaining comprehensive PII remains encrypted.

Even though they have a universal view key(s), the Government agencies don’t have broad access to the encrypted PII stored with the Recipient VASP because the data itself is with the Recipient VASP and is stored until requested by a government agency through the appropriate channels.

POC: Blind Sanction Screening Using Zero Knowledge Proofs

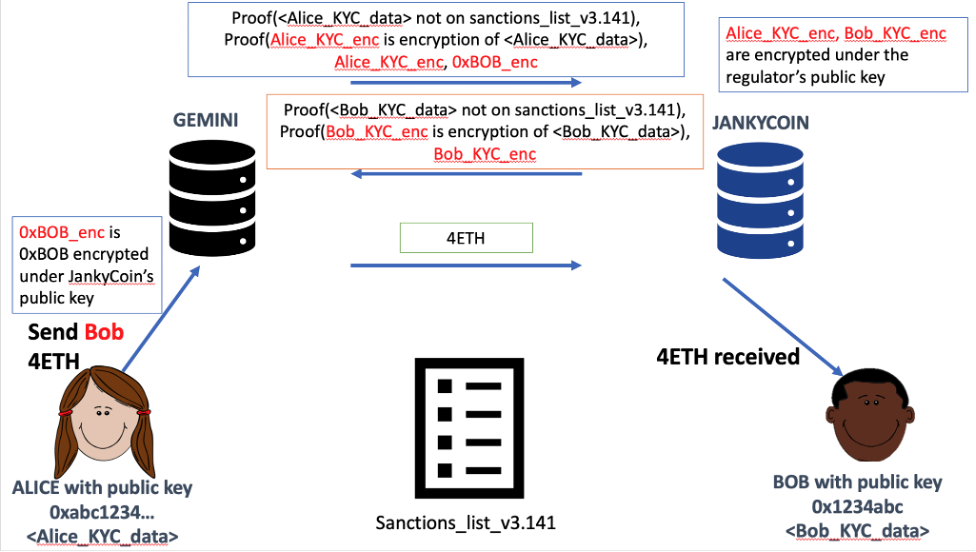

This proof of concept developed by the CanDID team at Cornell generates a “proof of non-membership in a sanctions list.” By checking this proof, both VASPs can do their due diligence on both the sender and recipient before allowing the transaction to take place. The solution is designed to be fully compliant with regulatory demands. For example, it allows the regulators of both VASPs to have complete access to the data of the sender and the recipient.

For a first prototype, the team scoped the problem as follows:

- Alice and Bob are two users and their respective VASPs, Gemini (perhaps a competent VASP) and Jankycoin (a less competent, less well-funded VASP), are both under the same regulator’s jurisdiction (e.g. both in the US) and use the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions list.

- The VASPs can collect the names, addresses and other necessary data from their users during KYC, so false positive matches off the OFAC list are negligible.

- The proof-of-concept performs a fuzzy search over the names in the OFAC list. This can be thought of as a primary screening, and if that gives a positive match, further screening can use more attributes about a user.

Using Zero Knowledge Proofs for Sanction Screening

The solution we implemented for the proof of concept envisions each VASP to generate a proof of non-membership of its user, i.e., Gemini generates a proof for Alice, and Jankycoin for Bob. As shown in the picture below, these proofs are exchanged and verified by the two VASPs.

The proof consists of two sub-proofs; the first is a proof to show a user’s KYC AML data is not on the sanctions list. The second proof shows that the KYC AML data used for the proof is the same one as encrypted under the regulator’s key (to be saved for when a regulator, such as OFAC or FINCEN, wishes to look up a particular user).

Security Guarantee

Both VASPs only make transactions once they’ve ensured due diligence is done. Data is still stored for regulators. All VASPs learn user information on a need-to-know basis, so the breach of JankyCoin’s database does not compromise Alice’s data. Each transaction contains an additional audit trail recording the version of the sanctions list used. Full confidentiality over communication channels for sanction checks

Security Non-Guarantees

We assume VASPs are not malicious and that the VASP is honestly presenting KYC data for its own client. We also assume that Gemini uses the correct name for Alice and that Gemini learns Alice’s PII data. Together, these assumptions are a potential stepping stone to using Decentralized Identities (DIDs),perhaps including anonymous credentials with the same security guarantees around OFAC list non-membership, to prove Alice’s identity to both VASPs.

Alternative Options for Proof Generation

The most thorough solution, and the one we propose, is to generate zero knowledge proofs. The benefit of this approach is that the scheme’s security relies on strong cryptographic guarantees, while the downside is its (somewhat) high cost today. (We note that a range of opportunities exist to bring down the cost that we have not yet explored.)

More performant alternatives exist if such a system is to be deployed imminently. One option is to leverage secure enclave and/or Trusted Execution Environments to access the list and run the checks through native enclave code. This approach is extremely cheap but would require placing some amount of trust in the hardware manufacturer.

Conclusion: How the Proposed Solution Preserves Privacy While Complying

This whitepaper proposes that Travel Rule compliance can be achieved without exposing VASP users to unnecessary privacy risks. Personally Identifiable Information (PII) of cryptocurrency senders, as well as associated blockchain attribution data, do not need to be exposed unencrypted simultaneously during transmission.

Encrypted envelopes and Zero Knowledge Proofs can work together to allow entities to comply with the relevant regulations while protecting user privacy. This proposed solution is better than the status quo because database leaks are less likely to be catastrophic for user PII since data is stored in an encrypted format.

The Travel Rule requires that information needs to be retained by each VASP but it does not have to be viewed by the receiving party nor does it need to be stored in clear text. This solution is a stepping stone to using Decentralized ID to prove Alice’s identity to both VASPs while not compromising her PII.

We have demonstrated that PII and transaction IDs of the sender do not need to be exposed simultaneously to comply with the Travel Rule and AML obligations. By separating the sanction screening of the legal person from blockchain Know Your Transaction (KYT) obligations, the receiving VASP can comply with the FATF guidelines while segregating the data elements during screening. Sender PII and addresses do not need to be exposed simultaneously to perform risk-based processes.

Links and Resources

CanDID Whitepaper

TRISA Whitepaper